Adam Blatner

Words and Images from the Mind of Adam Blatner

Why My Mother Threw Out My Comic Books (Part 3 of 3 Webages: The Comics after 1955)

Originally posted on June 12, 2009

Posted 3/5/2010 (This is based on a talk given 6/12/09 to the summer session of the Senior University Georgetown.)

In Part 1, the history of comics from 1890s through around 1949 is summarized briefly.

In Part 2, the national pressure to reform the excesses of comic books and the adventures especially of the EC comics line in all this.

In this Part 3 we’ll talk about a few of the high points of the history of comics since 1955. In fact, this history is extensive, and this webpage simply wraps up the story that began with the invention of comic strips and then comic books (see part 1); and then had a small crisis in its development (in part 2), which I discuss with a bit of focus on the events associated with the EC lines of comics. Some othe philosophical and social questions will be addressed—though no final answer is offered.

MAD Continues

In 1955, MAD comic book was changed in format to a black-and-white magazine, thicker, costing a little more (25¢). By this time the “Alfred E. Neuman” “What? Me Worry?” face had become almost a logo.

MAD (now) Magazine continued its satirical poking fun at movies and other mainstream trends and developed enough of a following among teens and adults so that it has become almost a cultural institution. It has kept Bill Gaines’ publishing activities alive for years and made him millions. So although EC comics for the most part folded, there’s this happy ending. What about the rest of the comic book world?

The Silver Age

The Congressional Hearings and the first Comics Code marked the end of the Golden Age of Comics, so labeled by a variety of comic book historians. This wasn’t all due to Dr. Wertham’s testimony, though; the growing power of television was a big part. Many comics, such as the Disney Comics, were hardly bothered. Nevetheless, in a rather complex story involving Stan Lee as publisher and Jack Kirby as a major artist, Marvel Comics and other publishers began to create new characters, superheroes, but now taking on a few interesting twists:

1. The heroes were more psychologically complex, often embodying some interesting quirks that affected their general mission. This made it possible to add some twists in the plot. (I’m reminded of the later character of the teen Marty McFly in the Back to the Future movies in the late1980s, who, given the benefit of time travel, does well, but also gets in trouble because of his character flaw, a “counter-phobic neurosis”: If challenged as weak or frightened, he feels compelled to engage in just the dangerous action that he fears, to prove to himself and others that he’s not frightened: Sometimes this backfires, generating more dramatic tension in the story.)

2. There’s a move more into the cosmic and interdimensional, and the theme of the activities of gods—while not confronting mainline religion—still open the question of there being vast cosmic potentials being dealt with on a grand stage. Some hints of this abound in written sci-fi literature, and in the emerging Star Trek and other sci-fi movies of the 60s and 70s.

3. There are occasional suggestions that the characters (and hence the artists) acknowledge the existence of the readers as audience, and sometimes even kid themselves and their own medium a little.

The Marvel characters of Kirby have become quite iconic! In this picture of the artist at work you can glimpse some of his more famous creations, including the Norse god Thor (with his hammer), Aquaman, Spider-Man, the Silver Surfer, and so forth. (The story on the left was made into a movie a few years ago!)

I discern in not just the drawings of this Silver Age comics, but the cultural response to them a process of “re-mythologization” (what a mouthful!)—an opening to the mythic dimensions that people do subconsciously. (The analytical psychologist and psychiatrist Carl Jung spoke to this aspect of the mind-in-culture, and the comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell helped explain the pervasiveness of this phenomenon.)

A number of other cultural trends weave together, and we can see mythic elements in so many aspects of culture, from the series of Lucas’ Star Wars movies to the more recent Harry Potter series of books. Part of this speaks to a hunger for re-enchantment, a participation in the intuitive, imaginative, and emotional dimensions of consciousness-raising. IThe culture for a century or more had perhaps drifted over-much towards the valuation of the rational and the marginalization of the non-rational and trans-rational dimensions. Part of the psychedelic and hippie revolution fed into and expressed a deeper cultural expansion of the category of spirituality—which differs from mere superficial religiosity. New religions from the East have fertilized the field and what is emerging is a more interspirtual range of phenomena. (See other articles on this website that address spirituality.)

Underground Comix

Another emergent cultural stream in the mid-late 1960s was the counter-culture, centered on the Haight-Ashbury Street intersction and district in San Francisco, it was a center also of drug culture, hippie culture, near to the Rock concert emporia, and so forth. Many of these trends were going on in many other urban centers in the USA and some overseas. The idea of self-publishing comics that were distinctly non-code, non-mainstream, became manifest. It was an era of the anti-Vietnam-War, pro-civil-rights struggle that expanded at the beginning of the 1970s to inclued feminist stuggles, gay rights, and other liberation ideas. The comix were flagrantly sexual—near pornographic—, celebrating marijuana and other drugs, violent, outrageous, appealing to the urge to transgress, to shock, to probe the edges of society’s norms.

From this culture emerged a number of artists who

have become more recognized in a variety of ways. Robert Crumb’s semi-depressive and perverse worldview has become more mainline in the last decade, his cartoons, sometimes co-drawn with his wife Aline, appearing in the New Yorker and other magazines.

Art Spiegelman was another underground artists whose venture into the form of the graphic novel—Maus—an exploration of his relationship with his father, a Holocaust Survivor, and his telling his father’s stories of the Holocaust, produced a stark, chilling reminder of the true horrors that made the horror comics seem tame. It was first serialized in the underground comix, Raw, and then granted a special Pulitzer Prize in 1992—a recognition that sequential art, graphic novels, might constitute a type of acknowledged literature! (More about graphic novels further on.)

Re-connecting to the EC Comics

Interestingly, Spiegelman wrote recently in a somewhat autobiographical illustrated book his own background and influence of his growing up with MAD comics and how those pictures influenced him:

Anyway, one of the points to be made is that comics rebounded, even with the code. Indeed, the history of comics after the 1960s has expanded into many different arenas:

Graphic Novels

As mentioned above, Maus broke some ground in the sphere of recognition. However, it was certainly not the first graphic novel. Indeed, a few of these had been tried around 1930s:

One was titled “God’s Man,” and another, by the popular comic strip artist Milt Gross, was one of my favorites: He Done Her Wrong. Most graphic novels have a variable amount of written dialogue in word-balloons or added narrative, but this particular novel is among those—and one of the first in this sense—to have absolutely no words. It’s a classical melodrama, “The Great American Novel” being its subtitle. Funny! Charming. Graphic novels and autobiographical pieces began coming out more frequently after the 1970s, and the size of that section in the library continues to grow. Many are really for adults rather than children. Yes, a few have more sexual content, but by ‘adult’ I refer more to addressing the complexities of illness, adolescence, relationships, politics, and so forth.

Art

In the mid-late 1960s Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein used themes from comic books—some drawings lifted directly from certain panels, or a combination of them—and these then were introduced with controversy as fine art. The point over the last few decades is that what is considered fine art is no longer able to be distingushed from popular illustration, advertising, the icons of media, and so forth. In these two panels, on the far left is an example of a Lichtenstein painting, and then to its right a satire by a comics artist, commenting on the nerve of the Museum of Fine Art in celebrating this trend without fully admitting that comics artists themselves are as much artists as those who have inveigled themselves “officially” (or successfully) into that field. I will say that there are some modern graphic novels that impress me deeply as high art, such as The Arrival, by Shaun Tan—-(another wordless book)—much finer in my opinion than 90% of what is so considered by academics and art merchants.

Comic Book Collecting

Very few kids in the mid-50s consciously collected comic books, thinking they’d be worth money some day. That did gradually begin in the 1960s and by the 1970s there began to be books published with prices noted for hard-to-find or top-quality old comic books. That has continued to the present. Apparently there was even a bit of a “bubble” in ths regard, some publishers publishing an overabundance of new lines, trying to make some money on those who were trying to build up collections. That bubble collapsed, but collecting, with less naive enthusiasm, continues.

Comic Conventions (Comic-Cons)

Another trend beginning in the 1970s was the idea of holding a convention of comic book fans, comic book artists, sales, and related paraphernalia. Starting in San Diego around 1970, the most notable one grew from 300 participants to over 100,000 in recent years!! In addition, there are now many spin-offs, regional and local conventions with smaller attendance. The point is that there is a significant niche market and sub-culture focusing on comic books.

International Developments (Manga, etc.)

There were comic strips started in Belgium (Tintin, by Hergé, in 1929) later turned into books; or the Asterix the Gaul series started in 1959.) Manga, a Japanese type of comic book has become very prevalent and read by all ages, with different sub-types appealing to different age groups and interests. Some of these are even pornographic. In Korea, Manha is similarly widespread. The point here is that comic books, graphic novels, sequential art, all have become much more prevalent in other countires in the last five decades.

Direct Sales

Also in the 1970s, comic book publishers shifted the marketing from it being more like consignment work, taking back those that didn’t sell, to direct sales. Deeper discounts to the middlemen, but no returns. This supported the emergence of a new institution—the store that specializes in comic books. Such stores often specialize also in fantasy role-playing board games such as Dungeons & Dragons, and the models associated with that activity. A few comic-books are still available at some supermarket or Wall-Mart-type stores in the books and magazines area, but not that many.

Comics Journals

Also beginning in the decades following the 60s, actual journals—semi-professional—surveyed the comics scene, including graphic novels, comic strips, comic books, and other media. There are a number of these now.. They carry articles about artists, themes, history, and commentary.

Academia

Comic books were lowbrow populist kid’s junk until a few academics beginning in the 1970s began to take this modality as a serious art form. That has grown in colleges and universities, and more than a few art departments address sequential art and cartooning along with the more traditional painting and drawing subjects. Books about comics—academic analyses, aesthetic, historical, political, are also emerging in increasing numbers.

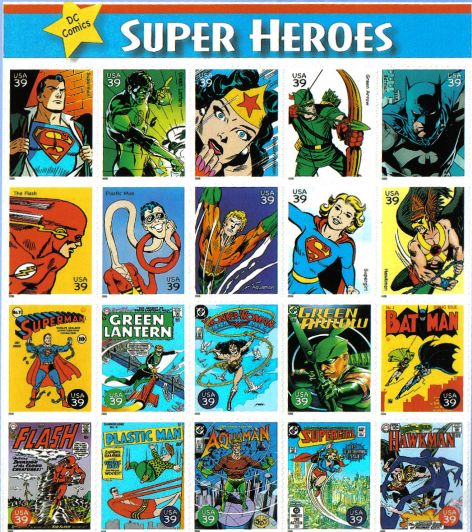

Entering the Mainstream

In 2006, the United States Post Office devoted a special issue to major super- heroes of the 1950s and 60s.

The themes of comics more recently are quite diverse, but my impression is that they tend to be caught up in violence and dark themes, often demonic. The art isn’t that varied, and in truth I am inclined to—indeed, planning to—offer my own version that invites people to imagine in a more positive fashion—see my associated website about the World of Almost-Real and the elves portrayed to the left.

Addendum:

In an article titled Super Powers: Turning a Dime Into a Million Bucks, in the Week in Review section of the in the New York Times’ Sunday edition of February 28, 2010, George Gene Gustines writes: Here is a lesson for all those parents who threw away their children’s comic books: Last Monday, a copy of Action Comics No. 1, in which Superman first appeared in 1938, sold for a record $1 million. (See cover pictures below.) That price was eclipsed on Thursday by the $1,075,500 auction of a copy of Detective Comics No. 27, where Batman made his premiere in 1939. Not bad hauls for comic books that originally sold for 10 cents each.

But this doesn’t mean that the masses who converged on comic book stores in January 2009 to grab Amazing Spider-Man No. 583, featuring President Obama, can trade in that issue for a deposit on a dream house. The recipe for what makes a comic book so valuable is a mix of content, rarity and condition.

Not surprisingly, the Man of Steel had it all. Superman was the trailblazer for all other superheroes, and fans at the time agreed: the alien visitor proved so popular that he took over Action Comics, which was originally an anthology of different stories and characters. “We had long theorized that Action No. 1 would be the comic to break the million-dollar barrier,” said J.C. Vaughn, the associate publisher_ of the “Official Overstreet Comic Book Comic Price Guide,” an industry bible. That first issue, Mr. Vaughn estimated, sold 130,000 copies; only about 100 remain. The buyers of those record-setting Superman and Batman comics, perhaps emulating the superheroes, have kept their identities secret. The condition of the Superman comic, sold by the auction house Comic Connect, was graded 8.0 out of a possible 10. Another copy, graded at 6.0, sold for $317,200 last year. The Batman book, sold at Heritage Auctions, was also graded 8.0. Fewer than 100 copies are believed to exist. A grade of 10 would signify a pristine book; an 8.0 indicates imperfections like a cover crease or Stress marks on the spine.

In the 1990s, speculators flocked to the comic book market, buying issues in the hopes that they would increase in value. But print runs for popular titles also greatly increased. In 1991, the first issue of a new X-Men title, written by Chris Claremont and illustrated by Jim Lee, sold more than eight million copies. “When you have thousands or millions of copies, it’s less likely a candidate” to increase in value, Mr. Vaughn said. The big money seems to be in first appearances. Last November, a 9.2-rated copy of Incredible Hulk No. 1 sold for $125,475 at Heritage Auctions; a 9.0-rated copy sold for $100,000 at Pedigree Comics. Here’s a look at some of those first appearances:

Smashing Debuts

References

Fingeroth, Danny. (2008). The rough guide to graphic novels. New York: Penguin/Putnam.

Fulce, John. (1990). Seduction of the innocent revisited: comic books exposed. Lafayette, LA: Huntington House.

Rhoades, Shirrel. (2008). A complete history of American comic books. New York: Peter Lang.

Ro, Ronin. (2004). Tales to astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, and the American comic book revolution. New York: Bloomsbury.

Shutt, Craig. (2003). Baby boomer comics: the wild, wacky, wonderful comic books of the 1960s. Iola, WI: Krause.

Skinn, Dez. (2004). Comix: the underground revolution. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press/Avalon.

Tags: comics

Leave a Reply