Adam Blatner

Words and Images from the Mind of Adam Blatner

Why My Mother Threw Out My Comic Books (Part 2 of 3: The Rise and Fall of EC Comics in the 1950s)

Originally posted on June 18, 2009

Posted 06/18/2009 (This is based on a talk given on 6/12/09 to the summer session of the Senior University Georgetown.)

In Part 1, the history of comics from 1890s through around 1949 is summarized briefly.

This webpage presents Part 2, describing the national pressure to reform the excesses of comic books and the adventures especially of the EC comics line in all this.

In Part 3 we’ll talk about a few of the high points of the history of comics since 1955.

My mom threw out my comics because, while not forbidding them, neither did she think highly of them. I now appreciate that she had been exposed to a good deal of negative publicity in the mass media, and she might have had some questions about comic books bein a bad influence. Anyway, I had gone away to college and left them in my bedroom closet; my Mom found the home too big too keep up and moved to an apartment; much of the household had to be gotten rid of—-so it may have seemed to her that my box of comics was not highly valued. (I estimate it would be worth tens of thousands of dollars today.) Reading for this presentation helped me understand the cultural environment of the time and to forgive her eveb more.

EC Comics

Let’s begin by remembering that Max Gaines was one of the key (if not the key) founder of the idea of the comic book in the USA around 1930. He had then a variety of ups and downs with various other publishers and businessmen, and in the early 1940s was publishing a few comics that were relatively wholesome. In 1947, though, he died in a boating accident and left his comic book business to his son, William (“Bill”) Gaines, then aged 22. Bill hadn’t really planned to go into the business, but under these circumstances, he tried to make a go of it.

In fact, while there were some back issues of Max Gaines’ “Picture Stories from the Bible” and such, those comics weren’t being produced any longer. Instead, Bill and his staff tried out a line of what had become a bit trendy in the late 1940s—westerns, romance comics, and crime comics, as well as funny-type comics (see right). EC at that time stood for “Educational Comics.”

Alas, these did not suffice. What were they going to do?

Bill Gaines joined with Al Feldstein as managing editor and finished with EC’s 1948-49 fare and embarked on a new EC line—the one that would make them both infamous and famous. This included three horror comics, a couple of shock/crime comics, and two science fiction comics. Then they changed the meaning of the comic book line so that EC meant “Entertaining Comics.”

Later, they hired the comic artist Harvey Kurtzman to edit two war story-themed books, and added them to the repertoire. They also hired very good artists, let them sign their name (which was relatively rarely done in the comic book world), treated them well, and paid them reasonably! As a result, the artists did remarkably able work! .

Here is a photo of Bill Gaines and Al Feldstein in 1950 with their new line:

What is Horrible?

The horror comics and crime comics seemed in keeping with what other people were doing at the time. It probably didn’t seem half as horrible than what

was coming into consciousness as the reality of the world—stories of the Soviet Gulags, the growing awareness of the reality of the Holocaust, and then there was the Bomb. If the threat of Nuclear Annihilation isn’t horror what is? Rember “duck and cover” exercises in school?

Meanwhile, there were scary shows on the radio—The Shadow, Twilight Zone, and so forth. And yet there were also forces that were trying to put a lid on it—and of course there always have been such forces.

Still, it was a time for scandal, for worry about “juvenile delinquency.” Marlin Brando’s role as “the leader of the pack” of Motorcycle Riders and rowdies in The Wild One (remember those early rock and roll songs that romanticized this alienated youth image?), was reinforced with the James Dean’s movies.

The political scene fed this hysteria: It was the era of Joe McCarthy, of loyalty oaths, of some people trying to go along with the government and keeping their heads low in the face of entertainment industry “black-lists.”

It was not only me who admired a number of the comic book artists in the EC staff: Historians of comic books have agreed that they were an especially able bunch. For example, there was Wally Wood, whose detailed drawings you’ll see below in some of the historical war stories. Jack Davis’ work was also impressive, and these two influenced my emerging cartoon style.

Here are the two war comics added to the line in 1951 with Harvey Kurtzman as the editor. Directly to the left with the tank is the July 1952 issue of Two-Fisted Tales, featuring articles not only about tank warfare in Korea and the battle for Saipan in WW2, but also one on the battle for Pell’s Point on what is now Manhattan island, and Washington’s strategic retreat that kept his army intact. It’s sad, because it tells the story of an overly-bold soldier who was killed—-but before he died, he remembered that important poem:

He who fights and runs away

May live to fight another day.

He who is in battle slain

Will never live to fight again.

Also in this same issue is a piece on the Alamo, as told through the eyes of a Mexican footsoldier. These shifts in perspective made these comics fascinating and mind-expanding.

I pored over the detailed art of Wally Wood in stories such as the one below on Julius Caesar. I was studying Latin at the time, and also reading about various military leaders:

I confess that I drew lots of pictures of Roman battle scenes and included these various war machines. It turns out that the EC staff were inclined to do a fair amount of research to ensure a degree of accuracy in their pictures. In these comics there were special issues on a variety of historical events, from the Civil War to other ancient battles. These comics enhanced my interest in history greatly.

Better Literature

I got started with science fiction from reading these comics in Junior High School. I used these images when I read the conventional books. EC

was unusual in running better stories. For example, they included comic book story (eight pages) length treatments of a number of the stories of acknowledged pioneer in writing fantasy and science fiction, Ray Bradbury.

Social Signifigance

I want to confess that some of the EC Comics—many of them—were fairly simplistic bits of horror and crime and perhaps qualified for minor trash. (They didn’t make me want to go out and do horrible things, but vicariously, I could blow off a bit of steam. This is one of the functions of what psychoanalysts call the defense mechanism of sublimation.

But EC Comics also often presented issues that were thought-provoking and controversial. In one sequence, in “The Guilty,” (below), a sheriff feels compelled to find a killer and arrests and coerces a black man passing through town into “confessing,” then setting up a phony event in which he makes the accused run for it and shooting him. Later it becomes apparent that this poor guy was innocent. While it was taboo then to consider that sometimes police were corrupt, innumerable events in the last few decades show this practice to have been more pervasive than anyone wanted to admit.

Other topics addressed by EC Comics included anti-semitism—and what happens if an anti-semite discovers that he was adopted and his original parents were Jewish?—; other kinds of prejudice; and so forth.

In some of the war comics, instead of simply presenting the Americans as heroic good guys—which it did in many cases—, there was some balance: War was often confusing for the troops on the ground, and this was true for those fighting on either side. EC took some of the glamor out of war. In a story about the Atom Bomb, it looked at the tragedy from the viewpoint of the civilians living in Nagasaki. This was aside from whether or not it was wise to drop the Bomb. It just “raised consciousness” about what all that meant.

In one of the EC comics’ science fiction stories, a monster appears—a mixture of godzilla, the thing, and King Kong—not really intentionally destructive at first, still, it is perceived as such and is harrassed by humans as a threat, finally killing it. Later, some adventurers explore the island and find (see right)…….

These twists and turns are typical for these comics and I enjoyed them.

One more example of social consciousness-raising: During an independence Day parade, a guy standing and watching the troops seems to be smirking and doesn’t take off his hat when the flag goes by. He’s beaten and killed by the mob:

So it might be argued that EC comics was a mixed bag. Certainly, a number of the comics had redeeming elements—such as:

MAD Comics

In 1952, Harvey Kurtzman was assigned as editor for a new approach, a comic that would poke fun at the various kinds of stories, advertisements, movies, and even the contents of other EC comics. (The first story appearing was a play on the horror comic.) MAD was remarkably successful and indeed, it was the only one, transformed into a magazine in 1955, to have survived the controversy and hearings and comics code events of the era of 1952 through 1955—to be described a little further on.

These comics were successful enough to have spawned knockoffs by other publishers, such as these:

Indeed, EC Comics was impressed enough to start yet another comic book with this same general format: Panic:

The Horror and Crime Comics

But, leading into the controversy, for all of the positives, there were also negatives. Indeed, some of the EC artists themselves felt uncomfortable with the edginess (in the sense of provocative gruesomeness) of some of the crime and horror comics. Not that EC was by any means alone in this. There were many other comic book publishers delving into the scarey-story genre.

Let’s say in behalf of the EC comics, that their line carried a level of self-mockery, a lightness, a sly self-parody. This postmodernist twist has become increasingly apparent in the “camp” styple of Batman television show in the 1960s, the “Get Smart” spoof on spy adventures around that same time, and so forth. The Addams family with its over-the-top morbidity (alluded to in Part 1) was another example of this.

In some of the EC Horror comics the traditional Grimm’s fairy tales were offered a different treatment as a “grim” fairy tale in which there might be surprise endings, such as the one about why sleeping beauty was sleeping and what happens when she wakes up (see pic on right):

In another “grim” fairy tale in a horror comic, the artists can be seen to partake of the kind of satire that would be more common in MAD comics . Here the Seven Dwarves— all their names a play on the actual Disney characters— Sourpuss, Dentis, Shyly, Coughy, Tired, Crazy, and Stupid—the last being a caricature ofArnold Stang— remember him? The point was that EC artists weren’t reveling in true horror so much as playing with it, neutralizing it, the way more recent movies like “Monsters, Inc.” make monsters—who by definition monstrous—into not-so-scarey-beings.

Trouble Brewing

Nevertheless, concerned parents, librarians, teachers, and others found the horror and crime comics of EC and other publishers offensive. Letters were being written. Groups were organizing comic book burnings (see right). Local law-enforcement agencies were seeking ways to keep this stuff out of the hands of congress. Editorials in newspapers were also expressing shock at the negativity of these images. So now we come to the escalating controversy, much of which centered on….

Dr. Fredric Wertham

Raised in Berlin, he became a physician, (M.D.) and then specialized in psychiatry —he was not a psychologist,, as some book have him labeled. He studied in Europe and then came to the United States in the late 1920s. Changing his name from Friederich Wertheimer, he was able to better assimilate, but he continued to speak with an accent that some said reminded them of the character of Doctor Strangelove in the movie by that name.

Actually, Wertham was a pretty middle-of-the-road fellow, on the liberal side on many issues, well trained for the time. He had done good work on brain damage and was gettng involved in criminology. He even opened the LaFargue clinic in Harlem for African-Americans (then called Negroes), and became interested in the causes of juvenile delinquency. And wouldn’t you know it, every delinquent kid he interviewed read comic books. Aha! (This is unfortunately a fairly obvious “sampling error”— because most urban kids and many rural kids also read comic books. And 95% of them didn’t turn into delinquents. But Wertham had a thing about comic books, and wrote articles and then a book in the late 1940s and 1950s..(To the right are articles Wertham wrote in Ladies Home Journal, Scouting, and Readers’ Digest:

Perhaps this was also associated with the promotion of a book that Wertham wrote that came out at the same time. Basically same argument. Pretending to be scholarly, it really wasn’t.

There were lots of “experts” and actual research that did not support Wertham’s bias: There wasn’t much evidence other that Wertham’s own interviews to support that comic books added significantly to the problem of delinquency. Indeed, it wasn’t that clear that delinquency itself had changed all that much from before comic books to the mid-1950s. Not that this stopped him: This was still an era in which experts tended to believe their own opinions.

<– Anyway, Wertham published articles and this book…

and of course when it came time to hold hearings on whether comic books were bad for you, it was politically understandable they’d get a “big name”—i.e., one known by virture of his publishing in popular journals—rather than experts who might give less “interesting,” and more academically qualified testimony. This tendency to aim for the inflammatory by mass media was noted also by Deborah Tannen more recently in a book titled “The Argument Culture.”

It should be noted that the Kefauver / Congressional Hearings of which we’ll hear more soon were a political response to a brouhaha by a variety of do-gooders, such as the “Legion of Decency.” (There’s a word you don’t hear much anymore—“decency.”)

Also, it must be admitted that by 1953 or so, the various comic book publishers were pushing the edge of respectability, were gradually upping the shock value. Well, we know now that this was happening in fine literature, and books like “Lady Chatterly’s Lover” .had not yet escaped the censor’s power (That book as well as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and Fanny Hill was held to be not “obscene” by the Supreme Court in 1959) Playboy was about to publish its first issue. But people thought comic books were about little kids. (That teens and adults read them was still overlooked.)

So, as we warm up to the next episode in this history, I am reminded of Shakespeare’s lines spoken by Marc Antony, the famous speech at Julius Caesar’s funeral: “…The evil men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones.” In spite of the many positive features of the EC comics line, those horror and crime comics were going to do ’em in.

The Congressional Hearings

Estes Kefauver, who had run for the Presidency in1952, was also known as a crime fighter. He had held hearings on organized crime a few years before, so it was an extenson of this that his committee also met in New York City to investigate comic books.

They had several people testify. Bill Gaines—against the advice of friends who said that he should keep a low profile and let it blow over—volunteered to speak out against censorshi. (Big mistake.) They told him they’d call him early, but spent most of the day and early afternoon listening to Wertham go on

and on. When Gaines finally spoke, he was tired and annoyed and got flustered when they confronted him with the sheer tastelessness of some of the covers that Wertham had objected to in his book. (The picture of the needle threatening the eye isn’t one of EC’s comic stories, but the cover to the righ closer to the center, alas, is—>)

It was a publicity thing, of course.. And it satisfied the passions of the do-gooders. At the end, the Congressional committee suggested that the industry police itself, develop a comics code, which it did. And it spread the word what the new standards would be. In fact, this served the interests of concerned parent groups, who were active locally. That would be where the real action happened—not from the top, but from the pressure of

people on the stores, on the distributors, from churches and PTAs and others. For example, Kids were encouraged to trade in (“swap”) “bad” comics for “good comics.” –>

Other communities collected comics and burned them! Trashed them! Some kids tried to protest, saying this was like the Nazi book burnings, but folks didn’t believe them. The main result, though, was the production of a new “Comics Code”:

These were then sent to major marketing chains (grocery stores),

drug stores, news chains, wherever comic books were sold, placed in libraries, and the blue book explained how to use the yellow book.

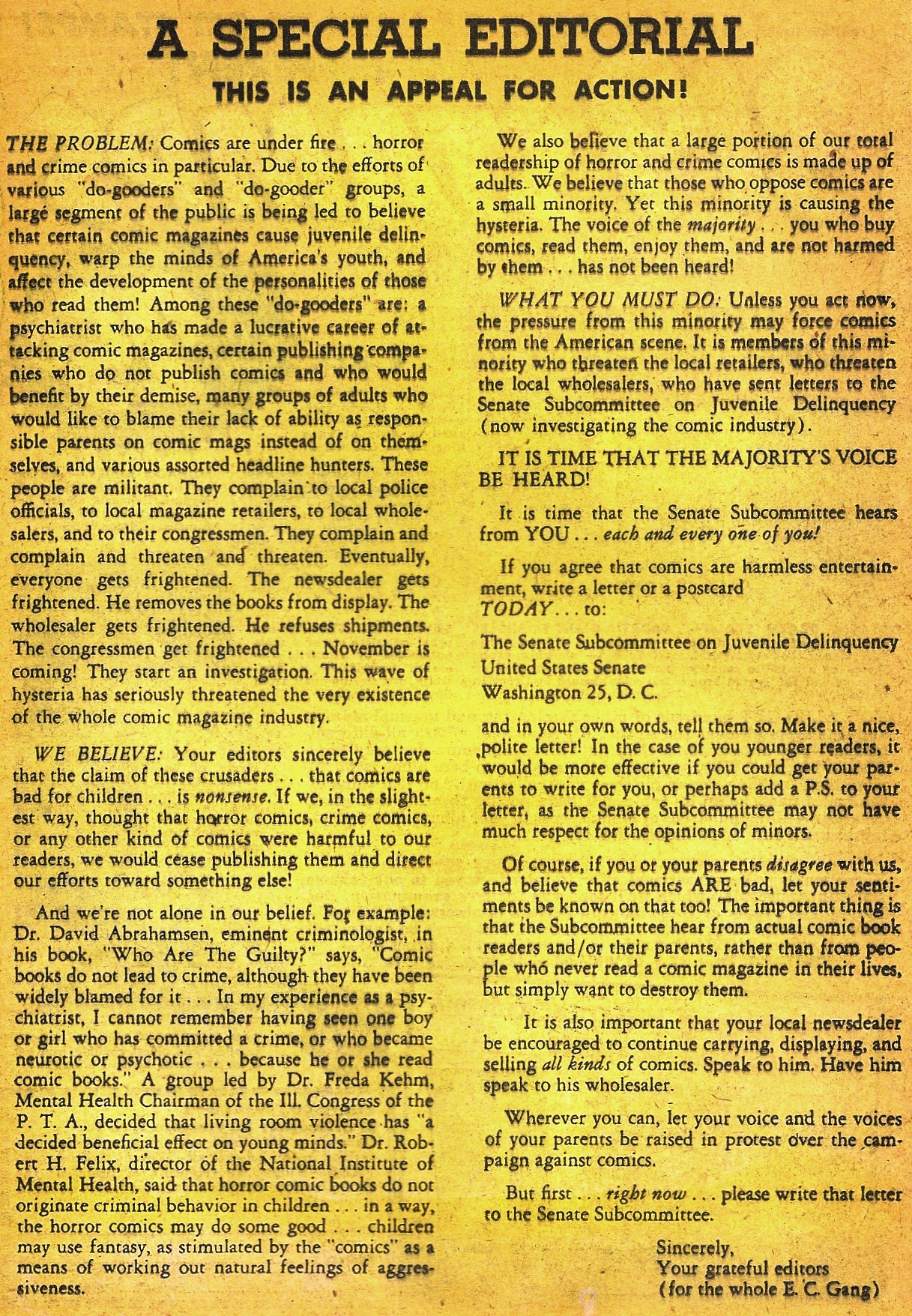

EC Fights Back

During this campaign, the publishers sought to challenge the attempts to quash the line of books through serious and playful means. They included scenes in their comics that poked fun at those who blamed things on comic books. They noted that repression of literature was common in communist Russia. And as things boiled to a head, they pictured themselves playfully as victims, being rounded up or forced to peddle comics like drugs.

I love the eyes on this doctor. Is it a poke at Wertham?

Well, something must be to blame for our kids not wanting to follow our commands to be good, to maintain “law and order,” to knuckle under. Scapegoating is as old as humanity. Or maybe blame the communists!

In another spoof, Harvey Kurtzman, the editor of MAD, showe the artists getting raided (below left). At the bottom of this webpage, there’s an open letter EC asked its readers to send to congress!

In fact, all the comic books were losing ground to another medium, television! So it wasn’t just the Wertham controversy, though some historians are inclined to blame him. In later years, Wertham denied that he was trying to impose censorship.

Because I too am a psychiatrist, an expert, and I too get tempted to make pronouncements about the latest in hip-hop and rap music, the nasty lyrics, the near-pornographic material available on television and in movies (recognizing that R-rated doesn’t really keep kids out), the way kids can get access to fully pornographic material on the internet, some video grames that are more sadistic and destructive, and many movies and even TV shows that are more gruesome, realistic, and scarey by far than anything they had in the 1950s—I’m tempted to say this stuff is bad for kids, too. Indeed, I’m pretty sure that it is for some sensitive kids! But where’s the actual scientific evidence?

EC Tries Again

They wouldn’t deal with EC. Finally, surrendering to the pressure, Gaines closed down the horror and crime comics.

Gaines gamely tried a “New Direction” of eight comic books (shown at left and below). Again, the art was good, the subject matter courageous and contemporary.

Part of what did EC in wasn’t congress, but rather that the general public’s outcry had come to impact the distributor. They returned his comics unopened.

Trying to Work Within the Comics Code

Gaines tried to get along within the boundaries of the comics code. As a denoument to this story, three examples of the power of petty bureaucracy.

In this first instance, a non-EC comic, Plastic Man, had PM’s assistant dealing with a villain who was also a shape-shifter, one who had changed himself into a pitcher of water.

Example 2: In an issue in Panic comic book, the other MAD-like EC comic, they ran a satire on Clement Moore’s well-known poem, A Visit from St. Nick.

First of all, remember that during the mid-1950s there was some popularity of “sick” humor, such as the little twist of putting a trap under Santa’s foot.

The artist, Bill Elder, was known for his little side jokes, too, and these can be found abundantly in this piece.

The Comics Code authorities found the end of this piece objectionable. It wasn’t just the bringing up the then taboo of divorce, but rather the stuffy judge felt the treatment of Saint Nick was (of all things) sacreligious!

Gaines went along with this, substituting the following (though he was exasperated).

The Last Straw

The final episode that clinched it was in Gaines’ science fiction story. In the future, there’s a Galactic Federation, sort of like Star Trek.

The guy in the space suit is the ambassador, sent to find out whether the life form on this planet is sufficiently advanced in consciousness to be welcome in that “higher” civilization.

This planet is inhabited by robots. It turns out that there were two kinds—orange robots and blue robots. The orange ones were the privileged ones. It was obviously an analogy to the racial divide in the USA in the 1950s. The visit revealed that under the skin, the robots were the same.

At the end of the story, the ambassador tells the robots they’re not yet ready, because of this folly of blind prejudice. Leaving, he takes off his helmet and reveals that he is himself black.

The judge said the last panel was unacceptable. Gaines argued with him: That the ambassador was black was the whole point of the story! Finally that penetrated the judge’s mind, but in a back-pedaling, the judge said that showing sweat was unacceptable! Gaines published the issue anyway and then closed down all publication—except for MAD comics, which he turned into a magazine—which was in turn not subject to the restrictions of the Code.

What happened next? See Part 3.

References (Part 2). (Parts 1 and 3 have their own references.)

Digby Diehl, (1996). Tales from the crypt: the official archives. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Geissman, Grant (Ed.) (and “The Usual Gang of Idiots”). (1997). Mad about the Fifties. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Geissman, Grant. (2005). Foul play! The art and artists of the notorious 1950s E.C. Comics! New York: Harper Design/ HarperCollins.

Hajdu, David. (2008). The ten-cent plague: the great comic-book scare and how it changed America. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Lent, John A. (Ed.). (1999). Pulp demons: international dimensions of the postwar anti-comics campaign. Teaneck, NJ: Farleigh Dickenson University Press.

Nyberg, Amy K. (1998). Seal of approval: the history of the comics code. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Reidelbach, Maria. (1991). Completely MAD: a history of the comic book and magazine. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.

Thompson, Don & Lupoff, Dick. (1998). The comic-book book (2nd ed.). Carlstadt, NJ: Rainbow / Krause. (Especially chapter 11, by D. Thompson, “The Spawn of M. C. Gaines,” pp. 288-313.)

Warshow, Robert. (2004). Paul, the Horror Comics, and Dr. Wertham (an essay written first in 1967). In J. Heer & K. Worcester (Eds.), Arguing comics: literary masters on a popular medium. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Wertham, Frederic. (1954, 200..). Seduction of the innocent. (New introduction by James. E.Reibman, Ph.D.)

Wright, Bradford W. (2007). Tales from the American crypt. (Pp.3-26). In J. Klaehn (Ed.), Inside the world of comic books. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

Appendix 1: Here’s a way EC struggled to keep active:

Tags: comics

Leave a Reply