Adam Blatner

Words and Images from the Mind of Adam Blatner

Why My Mother Threw Out My Comic Books (Part 1 of 3 Webages)

Originally posted on November 18, 2009

Re-Posted November 18, 2009 (This is based on a talk given on 6/12/09 to the summer session of the Senior University Georgetown.)

This presentation will involve three parts: First, a brief history of comic books from their origins to the late 1940s.

Part 2 will focus on the rise and fall of the EC comics, triggered in part by a nation-wide objection to what was seen as the excesses especially of the horror and crime comic genre—with some focus on the nature of EC comics, its efforts at fighting what its publishers felt to be censorship, and the final denoument. (It should be noted, though, that there were many other crime and horror comics put out by other publishers. For reasons to be noted, I had a special preference for the EC line, so its role in this grand cultural and art-business trend will be a focus. (Those comics, after all, are the ones my mom threw out around 1956 when I moved to college and she moved to an apartment.) Part 3 will note the rebound and briefly survey developments since around 1955.

Synopsis

Comic books have become a significant part of not only American culture, but also internationally. They emerged in England and America, first as newspaper comic strip supplements, beginning in the late 1890s, and then in bound form as cheap paper- magazine format in the early 1930s. Comic books became a staple of the childhood of millions of American children in the 1940s. However, starting soon after their creation in the early 1940s and increasing into more of a movement among concerned parents, librarians, and others, there was an increasing outcry against their possible bad influence on youth. In Part 2, on another linked webpage, this concern over the bad influence of comics led to congressional hearings. This presentation focuses more on the rise and fall of one of many comic book publishers, Bill Gaines, and his line of EC comics —which I confess were among my favorite and significant influences in my own development of cartooning as one of my avocations. In Part 3 the follow-up of this controversy leads into the continuing development of comic books as they move from children’s “trashy” entertainment into realms of art and literature. Finally, although I’ve already pretty much forgiven my mom—-she did so very much and was so very good to me in many ways—still, preparing this series helped me understand the social milieu she was living in, the historical circumstances, and that has helped me forgive her even more.

History of Comics

This is an extensive story—see the references below—so this presentation only touches on a few highlights to set the stage.

Of course there were cartoons and illustrations in newspapers and pamphlets in the early 19th century, and even some precursors to comic strips, in the sense of their being “sequential art.” Comic strips in newspapers, though, were made possible by improvements in printing—especially, the printing of colored drawings. A breakthrough happened in 1894 with the invention of the Hoe Color Press (picture at left), a printing machine that allowed for the creation of color supplements, and this meant comics as a vehicle for attracting greater leadership by such newspapers as the Pulitzer and Hearst lines in major cities.

This printing press made it possible to generate a more vivid yellow color, and in turn this led to the characterization of new rascally immigrant boy, the subject of a new cartoon strip: The Yellow Kid. This strip playfully mocked the odd slang and dialect of the slum kids and their adventures, of whom the Yellow Kid was one.

Getting a more vivid color, such as yellow, was a shift in the vividness of emerging comics formats.

First in thePulitzer and then in the Hearst newspapers, this strip also gave rise to a related term, “yellow journalism. This is because the newspapers in that era were sometimes creatively muckraking in a positive direction, but also were willing to engage in a kind of distortion of the facts that served the political preferences and interests of the publishers. Today it might be considered to be more like the kind of tabloid journalism in which the facts are not always checked at their source.

In the ensuing decade, a variety of comic strips were created, and some of these involved rather skilled feats of artistry and composition. Lionel Feininger has more recently had his cartoons revived in books that speak about his near-surrealistic approach: This below is from 1906.

Another artist drew the character “Happy Hooligan. His cartoon in 1902 (below) also includes characters you might recognize: The Katzenjammer Kids and their mother.

Also around 1906 Windsor McKay began to produce his series of amazing, surrealistic comics. One was called “Dreams of the Rarebit Fiend”—featuring another kind of surrealistic expression of the dream-world; and also there was an ongoing adventure, quite elaborate, of a little boy named Nemo in his dream-life: “Little Nemo in Slumberland.” (Below.)

Historians of art as well as comics have declared that his art and that of some of McKay’s contemporaries are as worthy of respect and consideration as fine art as the work of many whose paintings and drawings have traditionally placed their works in that more refined arena.

The history of comic strips is extensive and this is meant to just give a taste. Suffice it to say that many characters were developed, and there are many books now about the history of comic strips.

Another development in the 1920s was the emergence of pulp fiction, and extension of the “penny dreadfuls” several decades earlier in England, and the “dime novels” in the United States. These were prose, with illustrations being mainly on the front covers.

Adventure stories, horror, science fiction, all evoked the thrills of movies and fantasy. The Amazing Stories at the lower left issue (of the bunch of covers on the right) featured one of Buck Rogers’ adventures!

In 1929, though, this was turned into a comic strip!

Other characters who entered the comic strips included Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy. Many comic strips and then comic books would follow. It was timely, because crime movies about gangsters such as Little Caesar and Public Enemy were especially popular.

The next step led into the comic book!

People would save and re-read their comic strips. In 1933, Max Gaines (who was the father of Bill Gaines who later is featured in Part 2 as the publisher of the EC comics that was one of the centers of the controversy over comic books and also one of the founders of MAD comics and later MAD magazine) was himself arguably the inventor of the idea of the comic book.

In 1933, Max Gaines was working for Eastman Color Printing company and it occurred to him to compile comic strips into a booklet format and sell these to businesses to give away as premiums.

This was done in the case ofFunnies on Parade, which was compiled and given away as premiums by Wheatena (a hot cereal, still available in some outlets). It seemed successful, so it was followed by Famous Funnies, tried selling them at newsstands and found they sold well.

Then he convinced Dell Publishing to releasePopular Comics, which featured the first comic book appearances of various newspaper comic strips, including gasoline Alle, Dick Tracy, Terry and the Pirates, and Little Orphan Annie, among others.

The next step was the development of the idea of the superhero. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster had been working up a number of comic characters since 1934, including the one who evolved into Superman. Finally DC comics picked it up and featured him in 1938 in Action Comics. (A mint condition of this first comic recently sold for about $314,000 ! )

There was a good deal of business dealings back and forth among the publishers, but for our purposes, suffice it to say that a series of superheroes followed soon thereafter:

Batman and Robin was published around 1939: Captain Marvel came out in 1940.

Captain America and all the rest began to fight not only crime, but during the Second World War, against the Nazis, the Japanese military, spies, and other nefarious influences.

A psychologist suggested that a woman superhero would be empowering for the many women who were becoming involved in the war effort, and so Wonder Woman began. in 1942.

One thing that was great about these guys is that they took on Hitler in his lair.! (Stalin, too, in the beginning—-until he became an ally!)

Comics began to be produced in great numbers. This was the “Golden Age” of comic books. Radio had become mainstream, too, since the 1920s.

Kids gathered around the radio to hear the Adventures of Superman, and also other crime fighters, such as Gang Busters, The FBI in Peace and War, and many other programs.

During the war, the comics appealed also to teens and many servicemen —-many of whom were not only young, but also bored.

The government realized that sequential art—i.e., comics—offered useful ways to communicating practical information to a wider range of people. Thus, information books were issued in comic book form during and after the war —>

After the war, the theme of fighting bad guys continued. But the war being over required a new bunch of villains.

For example, Superman found himself dealing with new characters, (see far left) such as an elf-like fellow from another dimension, Mr. Mxyzptlk. Other comics began to put out Western comics.

Now, the plot thickens!

Comic books were not seen by everyone as harmlless. There had been voices raised by editors of newspapers (such as Sterling north, here on the left) since 1940 that these stories were bad for kids’ minds. Two developments increased this controversy—-the emergence of more flagrantly brutal crime comics and the beginnings of horror comics. Not that there weren’t prevalent trends for both these developments..

Crime stories had been around for centuries, and certainly became more prevalent, as noted above, in the 1920s. On the radio and in movies the theme had been explored at length. There were vigilante crime fighter shows such as The Shadow, The Green Lantern, and others, for example.

Horror comics hadn’t really gotten gruesome, but their roots were in the fascination with the morbid and the scarey—again, present for over a century in mainstream literature, from the early Frankenstein’s Monster story told by Mary Shelley through the writings of Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce in the 19th century. During the 1940s, Charles Addams, the cartoonist featured in the sophisticated New Yorker magazine, made his weird family rather popular—and in the 1960s it became the source of a television program (The Addams Family) (upper right) —followed by some movies, and also with several knockoffs, such as “The Munsters.” Movies in the 1940s also featured Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, and the Wolf Man.

We are warming up to a cultural clash between the forces of “decency” (you don’t hear that word that much anymore, do you?) and the forces that would corrupt our children’s minds. It was a continuation of the censorship activities of Anthony Comstock over a half-century earlier, an attempt of parents to control their youth. Actually, this struggle has gone on for millennia, and the ancients have writings that speak to this tension beween restless youth and more “stable” elders. Another way to think about this is as a recognition that what is called modernism in literature and the arts often involves upsetting the complacency of the middle class, of shocking the bourgeoisie. It’s a little harder to critique when it’s part of the “fine arts,” because the common folk hardly know what those trends are about. But when a popular medium clearly aimed at the children start to stretch the boundary, then parents groups, religious groups, and others get wound up about it.

So crime comics began to push the edges: The woman, frequently bound, with dress torn, vaguely implying sadistic sexuality. The sense that although lip service was given to how the villains lose in the end, it seems often that they get away with a lot and have fun being aggressive before they’re captured or done in.

Crime comics accounted for as many as one out of seven comics published. Other comics were a mix. There were the Disney characters, and the teen adventures of Archie. Classic

Comics had begun also in the early 1940s, and there were innumerable little kids and funny animal comics.

On the next webpage, we’ll focus more on a particular publisher and his line of “EC” comics. He, too, pushed the edge, and in the next several years, society became far less tolerant of comics.

Some comics were pretty innocent—the Disney comics, the Classic comics, the teen comics.

– – –

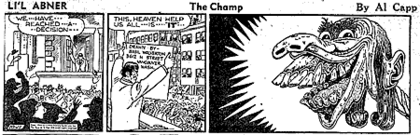

There was also comic gruesome-ness, and I was impressed with the contest in Al Capp’s then very popular Lil’ Abner” comic strip when he had his characters have a contest for the picture of the ugliest woman in the world.

Many people submitted drawings. Here was the winner, “Lena the Hyena.”: The cartoonist Basil Wolverton won, and drew similar pictures later in MAD comics—some were almost as horrendous.)

Another kind of gruesome was also cooking. I was a healthy, normal boy, which meant that I could get pretty gross. The gross songs in summer camp were funny, as were ghost stories. This photo of Al Jaffee and Bill Elder in High School— probably ten years older than me, but still in the spirit—also reflects that “boy” complex that was common for middle school guys. It sets the stage for how basically nice kids can celebrate their rebellious side vicariously.

In Part 2 we’ll discuss the rise and fall of EC and many other comic book lines in the early 1950s, and then in Part 3 we’ll talk about how comics evolved after the mid-1950s.

References

(Further references on the Part 2 and Part 3 webpages)

Benton, Mike. (1993). Crime comics: the illustrated history. Dallas: Taylor.

Carlin, John; Karasik, P. & Walker, B. (Eds.). (2005). Masters of American comics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press & Hammer Museum & Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Daniels, Les. (1995). DC Comics: sixty years of the world’s favorite comic book heroes. Boston: Bullfinch/ Little Brown.

Duncan, Randy & Smith, Matthew J. (2009). The power of comics: history, form and culture. New York: Continuum. (Really, a textbook! Many other references. Surveys the new medium, summarizes history.)

Gross, Milt. (1930, 2005). He done her wrong: the great American novel. Seattle: Fantagraphics Books. (Revised edition edited by Gary Groth.)

Goulart, Ron. (1986). Great history of comic books. Chicago: Contemporary Books. (Especially Chapter 18, The Wertham Crusade” pp 263-274)

Harvey, Robert C. (1996). The art of the comic book: an aesthetic history. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Jones, Gerard. (2004). Men of tomorrow: geeks, gangsters, and the birth of the comic book. New York: Basic Books / Persus Books.

Jones, Willam B. (2002). Classics Illustrated: a cultural history (Especially Chapter 21). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Krensky, Stephen. (2008). Comic book century: the history of American comic books. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books.

Lopes, Paul. (2009). Demanding respect: the evolution of the American comic book. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Simon, Joe. (2009). The comic book makers. Lebanon, NJ: Vanguard.

Wright, Bradford W. (2001). Comic book nation: the transformation of youth culture in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wright, Nicky. (2000, 2008). The classic era of American comics. London: Prion Books Ltd..

Tags: comics

It was the Green Hornet on the radio, not the Green Lantern. GL’s stablemate in All-American comics, Hop Harrigan, did get a radio show.