Adam Blatner

Words and Images from the Mind of Adam Blatner

Postmodernism Skewered

Originally posted on July 28, 2016

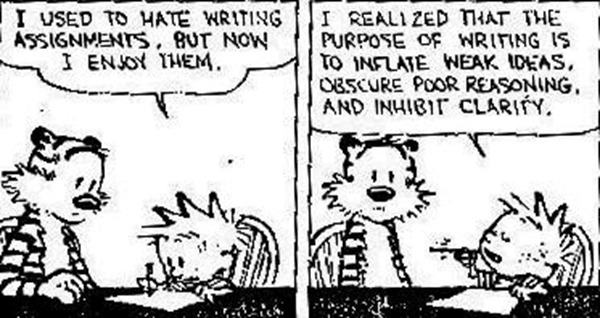

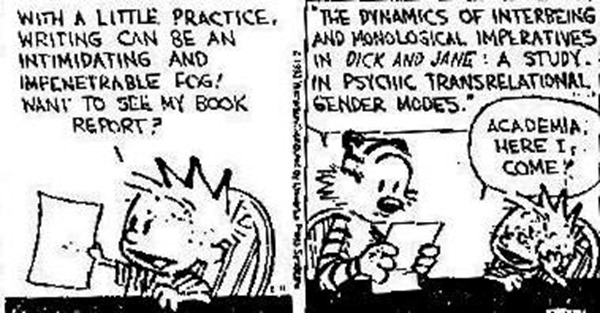

Bill Watterson, who wrote and illustrated the cartoon strip Calvin & Hobbs, noted that language itself can be obscure, and those who write about postmodernism are really good at being bad in this way. For example:

Actually, I rather welcome many of the principles of postmodernism, but those who write in this genre often appeal to those who are familiar with the jargon which obscures the arguments. Calving is a psychopathic brilliant kid, an alter ego to his creator. I love his work on the whole, but this piece gives me a chance to laugh and question.

In fact, Dick and Jane really carry the 1940s gender modes, which in 40 plus years would come in to question: Must girls always be like Jane and boys like Dick? No way! It notes that the “old fashioned” values of the “olden days” had a shine of being “the good old”—but women were really kept in “their place”—which, as sexist people believe, was where all right-thinking women wanted to be.

2 Responses to “Postmodernism Skewered”

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Categories

- Action Explorations

- Art (Mandalas, Doodles, Scripts)

- Autobiographical

- Book Reviews

- Current Events

- Essays and Papers

- Follies

- Foolin Around

- History

- Mind-Spectrums

- My Favorite Things

- Play and Spontaneity

- Psychodrama

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychology

- Psychotherapy and Psychiatry

- Scriptology

- Social-Depth Psychology (Sociometry)

- Spirituality and Philosophy

- Uncategorized

- Whassup?

- Wisdom-ing

- World of Almost-Real

- Zordak's Journal

Archives

- October 2021

- August 2020

- January 2020

- November 2019

- March 2019

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- October 2014

- September 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- December 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- September 2006

- December 2005

- October 2005

- February 2005

- December 2004

- October 2004

- May 2004

- July 2003

- October 2002

- September 2002

- August 2002

- July 2002

- June 2002

- August 2001

- December 1980

- December 1979

Some people believe academic writing (and especially in the world of postmodern thought) is so complicated to understand because academics are trying to be impressive or insular. But I wonder if there’s another, more subtle reason, too: The stuff they’re talking about is actually difficult to understand using language.

The problem, of course, is that postmodernists understand that every word means not just that word but many other things, too, based on your perspective — the old joke of “it depends on what your definition of is is.” If everything is relative, then writing about anything becomes almost impossible, like an infinitely recursive loop. And yet we are still driven to write, to at least attempt to capture the ineffable.

In my current academic endeavours (machine learning, situation research), researchers give their best to be as simple to understand as possible. I think there has been a shift towards writing with clarity and a style that relaxes the reader, just as university lectures here in Frankfurt are done with more interaction with the students, visualizations of the ideas and other things. Attempting to be especially smart by using complex words and sentences is not regarded as very nice in my time and place.