WHY LEARNING

TO PLAY IS

IMPORTANT:

AN UP-TO-DATE "DISORDER-SPECIFIC PSYCHOTHERAPY"

FOR PEOPLE

WITH PSYCHOSIS ACCORDING TO MORENO

Reinhard T. Krűger

Author’s address: (Riethof 7, D-30916 Isernhagen, Germany; E-mail: krueger.reinhard@htp-tel.de

Abstract:

In the 1930s

Moreno developed the “auxiliary world technique” for the disorder-specific psychotherapy of

people with psychosis. This method treats what he considered to indeed

be the central disorder of people with psychosis. That can be

considered by indications of neuropsychology, ego psychology, conflict

psychology as well as of psychodrama theory. Unfortunately, Moreno did

not mention something essential in the description of his cases: In the

disorder-specific psychotherapy of psychosis the therapist himself

needs to adopt a changed stance that goes beyond reality, a “trans-real

therapeutic stance,” and he needs to become more or less continually an

auxiliary ego and double of the patient. This changed trans-real

attitude of the therapist is the basis for an approach, adapted to

today's conditions of the treatment of people with psychosis, for the

emergency doctor, the psychiatrist or the psychotherapist.

Introduction

In this lecture I ll tell you about how I came to practice what I call a disorder- specific therapy in the treatment of psychotically ill patients by using a particular therapeutic stance; I’ll further describe how to apply this stance in practice and about the theory of the disorder- specific therapy of psychotically ill patients.

1. What are the effects of a disorder-specific psychotherapy in people with psychosis?

Disorder-specific therapy of people with psychosis can achieve important therapeutic goals:

1. It can improve diagnostics;

2. It can aid patients insight into their own condition

3. It can help avoid residential psychiatric care

4. It can improve the relationship between therapist and patient

5. It can reduce the cost of medication

2. My own journey of developing a particular therapeutic stance in the treatment of people with psychosis

During my training to become a psychodrama psychotherapist from 1971 onwards, I heard of Moreno's methods in the treatment of people with psychosis. Moreno has experimented with psychodramatic methods from 1936 onwards within the context of his own private clinic with 12 beds. There were no psychiatric drugs at that point in time. Moreno developed a method, which he named the "auxiliary-world" method. This is a particular form of psychodramatic individual therapy, by which a patient is treated by a team of several therapists. I will give one of his case descriptions here in a shortened version (Moreno 1975, 193 ff).

Case illustration 1: At the beginning of World War II a man with a small moustache on his upper lip came to Moreno's practice. Moreno asked him for his name. The man became angry: "Don t you know me?!" Moreno was shocked, but then he remembered: The wife of the patient had phoned and told that her husband believed to be Adolf Hitler. Moreno therefore immediately identified himself within the patient's symptom, his delusional belief: "Of course, now I recognize you! You are Mr. Hitler, Adolf Hitler!"

The patient complained bitterly that the man in Germany, who calls himself Hitler, was taking everything away from him, his soul, his inspiration, his energy. The man in Germany even pretends to have written the book "Mein Kampf". Moreno took hold of the telephone and ordered two male nurses to come. When they arrived, he introduced them as Mr. Goering and Mr. Goebbels. The patient had actually arrived at an inconvenient time. Moreno was due to speak to some students in a lecture theater. However he seized the opportunity with both hands and invited the patient to give a speech to his people. The patient followed this invitation straight away.

In the case illustration Moreno describes how he treated this patient in regular individual therapy sessions over a period of three months. During these therapy sessions, the two nurses who played the roles of Goering and Goebbels continued to play these roles without role reversal and without discussing it afterwards. The patient changed gradually during the course of this treatment. Eventually he shaved off his moustache, starting to cry bitterly while doing so, and later asked to be called Karl and no longer Adolf. After the treatment the patient, a master butcher, was able to integrate well socially, and a few years later returned to Germany.

I found these case examples from Moreno fascinating. But I knew my patients would never allow such a procedure. They would feel they were being made fun of. I did not even try it. Even so, the knowledge of Moreno's special method of psychotherapy with people who were psychotically ill, unnerved and tormented me. I know today that back then I had not yet recognized the central basis of disorder specific psychotherapy for psychotically ill people, namely, the changed trans-real shaping of the therapeutic relationship.

3. The different attitudes of the therapeutic relationship in the treatment of psychotically ill people

In the disorder-specific therapy for people with psychosis the therapist has to change his attitude towards the therapeutic relationship. I differentiate the psychiatric shaping of relationship and the disorder-specific shaping of trans-real relationship. I call this shaping of relationship trans-real, because the therapist stays neither in ordinary reality nor fully in the fantasy, but rather he moves beyond reality and fantasy.

The usual psychiatric attitude of relationship: In the psychiatric therapy of the psychotically ill the therapist and the patient get into a tragically blocked relationship:

1. The patient tells the therapist of his psychotic experiences or he or she behaves crazily.

2. The psychiatrist on the other hand, tries to empathize with the patient.

3. However, he realizes that when he starts to empathically relate to the psychotic experiences, that he himself is in danger of going crazy.

4. This causes anxiety in the therapist.

5. The psychiatrist therefore distances himself from the psychotic experiences with the help of the psychopathological terminology developed by Bleuler (for example: hearing voices, de-realization or depersonalization. "Do you hear voices?" "We call that derealization!" "We name that depersonalization!")

6. The psychiatrist more or less directly fights his patient's psychopathology, for example the hearing of voices.

7. Through this, however, the therapist takes on from a systemic viewpoint, the sole reality- playing role, and the patient takes on the sole craziness playing role. A mutually complementary blocked relationship develops between the therapist and the patient and results in a common resistance against true progress in therapy.

8. The psychiatrist acts out a counter-transference.

9. In the end the patient has only the choice between two negatives: Either he flees from all relationship into isolation, perhaps even into homelessness, or he blindly takes on the view of the psychiatrist and learns to live with his mental illness, takes the medication handed out to him by his doctor and excludes his psychotic experiences in his communication with the therapist. This is comparable to a traumatized patient who would not talk about his traumatic experiences in his therapy.

In spite of being a psychodrama therapist I myself used the usual modern social-psychiatric therapy during my first 25 years working as a psychiatrist. I worked hard. The patients recovered in parts. But I never succeeded in treating the heart of psychotic illness and the central psycho-pathology didn’t go away.

The trans-real attitude of the therapeutic relationship in the treatment of psychotically ill people

Twelve years ago I finally understood the basic principles underlying Moreno's disorder-specific psychotherapy of the psychotically ill and I became able to practice psychodramatic disorder-specific therapy of psychosis and to teach it to my therapeutic pupils too. It was a true “aha” experience, a creative jump in my understanding of psychosis!

In a working party of psychodrama friends on the subject of a therapy of psychosis we had the idea to replay Moreno's method psychodramatically, as it was reported by Raoul Schindler (Moreno, 1959, p.85; Erlacher, Farkas & Jordan, 1996, p.9):

Case example 2: At the beginning of the 1950s Moreno came to the university clinic in Vienna in order to demonstrate his method of therapy. However for the demonstration the psychiatrists had chosen a patient with a depressive stupor. The doctors were unable to reach this woman through questioning or by conversation as, due to her psychotic illness, she was mute. Despite this, Moreno refrained from seeing this woman prior to the demonstration. Schindler reports: "When the woman was led into the lecture theatre, she stopped walking after a few steps. But without hesitation Moreno stepped up next to her, greeted her and took her hand. Then he stepped up next to her and explained to her that the doctors in the lecture theatre were some kind of students, who should understand from her, her own view of her situation.

Moreno began to act as a double. By acting as a double the therapist doesn’t stay any longer facing the patient opposite, but he positions himself at the patient s side taking the same perspective as the patient. In Moreno’s case example of Adolf Hitler, I presume that Moreno did not just introduce the two male nurses: "Mr. Goering, Mr. Hitler! Mr. Goebbels, Mr. Hitler!" I think that Moreno himself turned towards the nurses and acted as a double of the patient: "Mr. Goering, we are waiting for you! Why are you late? And Mr. Goebbels, you too! Mr. Hitler here is waiting! I hope you’ll bring good news to Mr. Hitler!" Then the two male nurses began to act their roles. In the second case example reported by Raoul Schindler Moreno also created a scene by taking the same perspective as the mute woman at a concrete level and by looking at the audience side by side.

Schindler continues to report: Case example 2 (continuation): "Almost as a side remark Moreno asked her for her name. To our amazement she told her name as if she had no inhibitions. Moreno repeated her name slowly and found it beautiful. He tied an association to it, which I forgot and which did not fit. The woman corrected him, and he took on her view immediately, and offered an extension. Through this, a trivial conversation developed with the atmosphere of high importance, carried by an expression of personal interest and without any objectifying reasoning. The stupor appeared to have gone and a conversation about her life's situation developed. Moreno hardly ever asked questions, instead he offered her thoughts and ideas and let her guide him by her corrections. So actually it was him who was being helped by this.

Family members emerged who were trying to get away from her. Not she, but Moreno did not want to tolerate their refusal." In this working party with friends we applied Moreno's method in fictive role plays and also in the treatment of our own psychotically ill patients. Through this we recognized once again the central therapeutic element in Moreno's method, namely the changed trans-real shaping of the therapeutic relationship within the dialogue by acting as a double.

In his case examples Moreno forgot to write about the technique of dialog-by-acting-as-a-double as the the basis of his procedure in the therapy of psychosis. Probably he regarded it as a self- evident part of his auxiliary-world technique. In the dialogue by acting as a double the therapist does not ask any questions. To succeed in this requires a very inconvenient and difficult skill in fine communication, because normally people ask, if they want to know. Instead the therapist playfully takes part in the patient’s delusional production and actively verbalizes and names the experiences of the patient. During this, of course, the therapist repeatedly takes a wrong turn.

This gives the patient, who knows his reality better than the therapist, the opportunity to describe his view of things. The therapist lets himself be corrected again and again. Through this the patient becomes the one who knows and the therapist the one who does not. That is very difficult for a psychiatrist and you will have to train it! It is important to develop the art of failing.

When acting as a double the therapist as a catalyst takes part in the process of resolving the delusional conflict empowering the patient to orientate and to create. The dialogue by acting as a double systematically changes the patient’s experience of delusion into a role play of the delusion in the role of self. The therapist stabilizes the role play of the patient and helps to act it to its end. By this the patient wins the aspect of creator (Moreno 1970, S. 78) in his delusion and experiences himself as being self-effective.

While applying the dialogue as a double, the patient together with the therapist substantiates what belongs to the delusional reality and what not (see diagram, left lower quadrant). In addition they actively organize the sequence in time and the logic of the delusional reality. The patient, experiencing the doubling therapist in vain struggling for reality in the delusion, feels accepted in his central suffering and sees his own craziness like in a mirror. Thus the technique of dialogue by acting as a double paradoxically strengthens the insight of the patient in being ill. That isn t only a theory. I experienced it. And you will experience this paradoxical outcome in using the dialogue by acting as a double too. The increasing insight in being ill improves the therapeutic relationship and the therapeutic compliance, makes the patient more accessible for therapeutic interventions and so helps among other things, to avoid or to reduce psychiatric residential admissions and to save the use of medication.

4. The application of the trans-real shaping of the therapeutic relationship in practice:

I would now like to show you, how one can apply the trans-real shaping of the therapeutic relationship in a crisis intervention of emergency medicine. In the following case example the dialogue by acting as a double helped to avoid the use of force in the course of sectioning a patient and thus prevented additional traumatisation of the patient:

Case example 3 A doctor, a general practitioner, is called out to an emergency at night. In front of the patient’s house an ambulance as well as a police car are already waiting. In Germany it is the task of police officers in the worst cases to apply force in order to get the patient to enter the ambulance. The doctor is informed and walks through the house to the garden at the back. A 50- year old man is standing there looking up into the sky. He seems to strenuously observe something up there. The doctor positions herself next to him on his left and also looks up into the sky: "There are plenty of stars tonight." The man: "Yes." The doctor: "You have to be alert." The man: "Yes". The doctor: You have to be careful that the celestial body up there (she is pointing with her hand to the visible stars in the sky) does not crash down on to the earth."

The man: "No, there are U.F.O.s landing". He makes a big movement with his arm from the sky to the ground on his right. The doctor imitates the movement by doubling: "You are showing the U.F.O.s where to land". The man: "Yes, I am directing them in." The doctor: "You carry a lot of responsibility there. That is bound to be exhausting". The man sighs, continues to stare into the sky: "You can believe that!" The doctor also continues to observe the sky. Suddenly, she points with her hand to the left: "There, there is still another U.F.O. You forgot that one". The man: "Oh!" With a big movement of his right hand, he directs the U.F.O. to its landing place. After some time the doctor:" I cannot see another U.F.O. Do you see another one?" The man: "No". The doctor: "Can we go now?" The man: "Yes". He walks with the doctor through the house to the ambulance and sits down inside it without any resistance.

The policemen do not need to take any action. I understand the lines of action in psychodramatic therapy by a theory of the eight central techniques of psychodrama, a theory of creativity and a theory of the creative Ego. These theories enable to assign a special function and indication to each of the eight central psychodrama techniques.

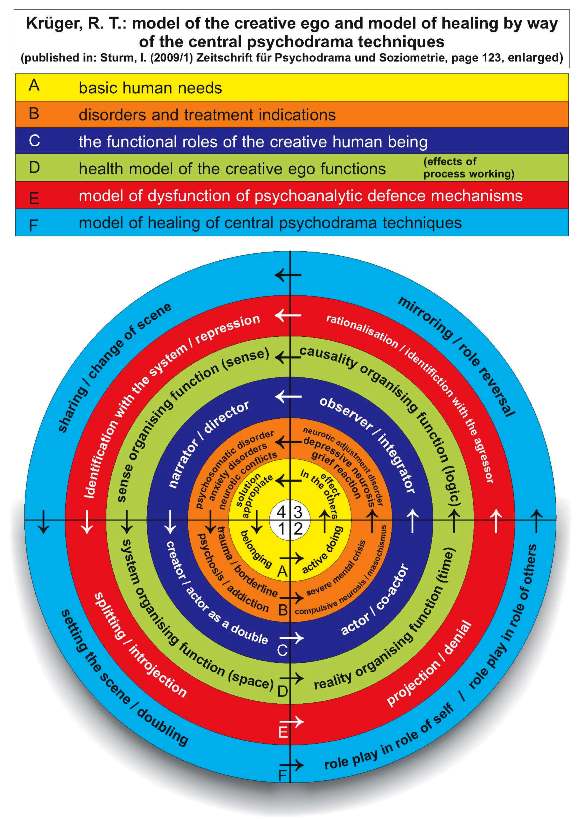

You see these in the picture to the right, in the circle F. From these theories it is possible to derive disorder-specific procedures.

|

You can see it in the picture in circle B. Psychotically ill people confuse their experience of reality caused by splitting, introjection and projection. You see these defense mechanisms in circle E at the picture below. There in the left and right lower quadrant you can conclude the central psychodrama techniques setting the scene, doubling and role play in role of self in circle F to the defense mechanisms splitting, introjection and projection in circle E and to be specially indicated in the therapy of psychotically ill patients in circle B.

These three psychodrama techniques specially strengthen the ability to organize the system and the reality of patients. You see it below in circle D.

The method of the dialogue by acting as a double is also valuable for diagnostics: Case example 4

During supervision an experienced psychiatrist describes the case of a 25 year old female patient with serious depression, states of anxiety, many serious suicide attempts and personality disorder. In the 5 year long therapy partly outpatient, partly inpatient there was no pointer towards a psychotic illness. Despite this and because of the chronic and severe symptoms of the illness, we came during the supervision to the conclusion that the therapist should try to apply the method of the dialog as a double. We practiced this together in a role play. In this the therapist took on the role of her patient, and I took on the role of the therapist. At the next supervision session the therapist amazed, happy and relieved reported that through the dialogue as a double she had for the first time gained insight into the decidedly destructive delusional experiences of her patient. For the first time in 5 years of therapy it was possible to appropriately treat the patient with psychiatric medication.

One can also use the dialogue as a double to start a longer individual psychotherapy. In that case Moreno’s “auxiliary world technique” will be included in the procedure. For doing so you have to change it, because the efforts required would go beyond any of today’s therapeutic settings. To do this, the therapist lets the patient concrete parts of his self and his delusional figures in the form of empty chairs and as hand puppets, playfully including them actively again and again into the psychotherapeutic communication of the patient s experience of everyday life, thereby going beyond reality. By doing this it is then helpful to divide the reality of the psychotically ill patient in which reality mingles with fantasy into "the ordinary-world" and "the dream-world" and to concrete the truth of the psychotically ill patient by placing two separate chairs in the therapy room as the "chair for the ordinary-world" and the "chair for the dream-world".

Case example 5

A 32-year old handyman, Mr. C., had been living for six months with the delusional belief, that he was being bugged and filmed in his flat. With the help of the dialogue by acting-as-a-doulble it was possible within the first therapy session, to convince the patient, that he should take medicine for four days as a trial "against his extraordinary great sensitivity". In the second therapy session Mr. C. reports:" It has become much quieter now. By the way, I also went to the police, but they said that they need proof or a witness." The therapist:" Yes, of course. That is reasonable!" Mr. C.:"But I don't have any! " The therapist: "Oh, yes, - shame!"

Four weeks later Mr. C. starts to doubt: "Perhaps I just imagined everything." But the therapist deliberately continues to create the therapeutic relationship as trans-real: "Do you think so!? I think that what you have experienced continues to be valid and meaningful." The therapist places a second chair to the left next to the patient: "I put this chair next to you for the part within you, which has experienced the bugging and filming. You can call it your dream-world. With nightly dreams it is also the case, that the content of the dream appears unreal during the day and totally true in the night."

During the next four weeks the patient with great effort draws up a record of his experiences and arranges them according to what he regards as "real," and next to that, what he called "imagined." The technique of the psychodramatic externally positioning of dream-world and ordinary- world makes it also easier for the therapist to playfully accept the co-existence of the two worlds of the patient side by side. Things are what they are. By doing so the therapist turns the patient's fight for reality back into an intra-psychically occurring fight with himself. This frees the therapist from his fear to become crazy himself and from acting out a counter-transference, and helps to resolve the tragic dilemma of the psychiatric shaping of the relationship.

5. Theory of the disorder-specific psychotherapy of psychotically ill patients

A disorder specific therapy of the psychotically ill, needs to respond to its central disorder. For psychotically ill people the central point of suffering is the confusion of experience of reality. An individual s experience of reality is always a subjective construction. Every individual organizes his experience of reality in the working memory of his brain. The working memory is that part of our brain, which works similarly to the working memory and processor in our computers. In the processes of conflict resolution our working memory integrates meaningfully our thinking, feeling, acting, remembering, perceiving and imagining.In psychotically ill people these processes of conflict resolution in working memory are disintegrated by strong affects and highly charged conflict material. Data will no longer be processed correctly. But a human being cannot stand meaninglessness. He desperately tries, therefore, to find meaning and will create in the extreme case, in form of a vicious circle, the delusional experience.

There are indications that in the psychotically ill the processing ability in the working memory is disordered (Frith, 1992; Goldman-Rakic, 1994). For example Schneider et al. (2007) have found in brain imaging studies of schizophrenically ill patients dysfunction (shown by lower activity) in relevant working memory structures. Interestingly these disturbances were smaller the more the psychopathological state of the patient improved in the following year, and on the other hand stronger the more it worsened in the following year.

In therapeutic psychodramatic practice, disturbances in the working memory are shown by psychotically ill people amongst others in that they cannot play. They do not understand for example, jokes or depth psychological analysis. They do not grasp as-if situations and metaphors as symbolic as-if-pictures, but understand these concretely. When psychotically ill people act a fairy tale in group therapy, then this will take 5 to 10 minutes, then it is over. Neurotically ill patients on the other hand need 60 to 90 minutes to do so.

It is obvious that the central disturbance of psychotically ill people cannot be healed if the therapist opposes the process of delusional development in the working memory of the patient. In the disorder-specific therapy of the psychotically ill, one has to go into the deficient integration process and into the process of delusional development, in order to change it.

The psychodrama psychotherapist understands the patient's delusion as an unconscious role-play. With the aid of the dialogue by acting as a double and the auxiliary-world technique he systematically transforms the process of delusion into a play. The therapist then tries, together with the patient, to take the role-play further and to take it to its end. The creative playing systematically imitates the processing work of the working memory in all its complexity and by this integrates disintegrated processes. The ability to play is the ability to create and to integrate by means of a process. In role-play in the role of self the patient regains the functional roles of the creator and of the double within his own life by organizing space and time (see circle C in the picture). So he regains control over space and time within his symptoms.

The psychotically ill patients shall not learn to live with their illness, but they shall regain the ability for self governance within their symptoms. If someone is able to start and to stop hearing voices of one’s own free will he or she is not psychotically ill. (This you can see in the case example 6 below.)

Moreno (1939), who developed psychodrama, and later others such as Benedetti (1983) and Casson (2004) made this method the basis of their method in therapy of psychosis. Fitting these theoretical considerations, in the 1940s and 1950s of the last century, when there were no psychiatric drugs, Moreno (1945, p.5) made two important experiences:

1. The therapist has to shorten the intervals between sessions in psychosis therapy depending on the acuteness of the delusional illness.

2. As a therapist it is important to consciously and repeatedly shape the therapeutic relationship actively trans-real, and to improve the self-governance of the patient in his past delusional experiences as well, even if the patient is symptom free at that time. The patient should not report from his delusion, he should act within it! Then, according to Moreno, the apparently healthy sick person usually tries to anxiously preserve his freedom from symptoms. But only if he undergoes this psychodramatic shock therapy, the patient is able to gradually integrate the psychotic contents and gain control over the roles, which he played during his psychotic decompensation (Moreno, 1939, p.3).

As long as such disintegrated parts exist outside of the control of the patient, similarly triggering events can bring the patient out of balance again and again (Moreno 1939, p.5).

6. Case example of healing of a psychotically ill woman using disorder-specific psychodramatic psychotherapy.

Case example 6: Mrs. E., a 35-year old good-looking, professional, intelligent, sensitive woman, had sometimes been hearing voices of neighbors in her very poorly soundproofed flat. These voices complained about how noisily she trod or how loudly she snored at night. During the last three years she had moved four times because of "poor soundproofing" of the flats. During psychotherapy together with the psychotherapist she worked out different parts of her Self opposing each other: on the subject level, the "friendly, soft Renate" and the "obnoxious person". In close relationships she was unable to maintain for long her friendly, conformist stance and with un-intentionally strong emotional outbursts, withdrew herself. On the object level, self-parts of her delusion existed as the neighbors whose voices she heard again and again. During the 28th session, the patient was by then symptom-free and also without medication, she reported that she was feeling well. In her relationship she had been able to talk in a new way openly with her boyfriend about the motives behind her actions and through this had been able to find error free friendly compromise solutions.

Mrs. E.:"In addition I now use ear plugs, because Robert snores so loudly. Then I don't hear any voices any more either. That would not be possible." The therapist is shocked by the naivete of the intelligent patient, nevertheless immediately he takes on a trans-real attitude: “And what do your neighbors say? Simply to use ear plugs? Then you don't hear them when they are complaining about you!. Don't you find that mean?"

Mrs. E.: "No, they don't really complain about me any more. They simply make nasty remarks and gossip about me!" The therapist positions at a short distance two empty chairs for "the neighbors", and asks the patient to describe these two. They are successful, intelligent, good looking and have no problems. The "presence" of the couple promptly evokes old feelings of inferiority in the patient: "Since my time at secondary school, I have felt insufficient with regards to people who have a good education, who are in control of their life, and with whom everything is okay." At the end of the session she emphasises:"Today you hit on a weak spot!"

According to my experience, psychotically ill people by playing in trans-reality integrate split-off parts of their Selves and so gain control over them. Those who have control over the figures of delusion and can let the puppets dance, as it were, can also stop delusional experience and are disorder-specifically viewed healthy.

Case example 6 (continuation):

For the 35th therapy session, Ms. E. comes back from a 14 day holiday looking exhausted. She begins disheartenedly: "I was on holiday with my boyfriend. Two days were like hell again. The voices were back. I thought that I would have to be admitted to a Spanish hospital." During the following conversation Ms. E. reports: "I had forgotten my tablets. Here at home I haven't taken them for a long time. During the fourth night I really heard the neighbour say to his wife: 'I know the company, she works for. That with her boyfriend is also a wild story!'" The patient further reports: "First I was shocked and full of anxiety. But then I thought. That is impossible, there can’t be someone of my company here! I became angry and deliberately thought about a lie: “And certainly you also were with me in the Kindergarten in Celle!” Ms. E went on: I repeated this sentence again and again. And then the neighbour really said to his wife:' And you know, I also was with her in the Kindergarten in Celle!' Then I put one more on top and thought: “Yes, and then my mother was on holiday together with your mother last year in Turkey!” There really came the voice of the neighbour saying: " By the way, my mother was on holiday in Turkey together with her mother, too." Then I realized that I had control over what happens. That was a big relief!"

Upon enquiry by the therapist, the patient confirmed that she herself had so far not been aware of this: "No, from then on there was silence. I never again heard anything from the room of the neighbours." Mrs. E since three years lives without taking any psychochemicals and has been without psychotic symptoms.

References

Allen, Jon G.; Fonagy, Peter; Bateman, Anthony W. (2008): Mentalizing in Clincal Practice. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington

Benedetti, G. (1983): Todeslandschaften der Seele. Psychopathologie, Psychodynamik und Psychotherapie der Schizophrenie. Gottingen

Casson, J (2004): Drama, Psychotherapy and Psychosis: dramatherapy & psychodrama with people who hear voices. New York: Brunner-Routledge.

Erlacher-Farkas, B. und Jorda, Ch. (Hrsg.) (1996): Monodrama. Heilende Begegnung. Vom Psychodrama zur Einzeltherapie. Wien.

Frith, C.D. (1992): The cognitive neuropsychology of schizophrenia. Hove, England UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Goldman-Rakic, P.S. (1994): Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. Journal of Neuropsychiatry Clinical Neuroscience 6, S. 348-357

Krüger, R.T. (1997): Kreative Interaktion. Tiefenpsychologische Theorie und Methoden des klassischen Psychodramas. G”ttingen

Krüger, R.T. (2001): Psychodrama in der Behandlung von psychotisch erkrankten Menschen. Praxis und Theorie. Gruppenpsychotherapie und Gruppendynamik 17, S. 254-273

Krüger, R.T. (2001): Das Lachen in die Psychiatrie bringen!?" - Entwicklung von Raum und Zeit in der Psychotherapie von psychotisch erkrankten Menschen. In: Kruse, G. und Gunkel, S. (Hrsg.) (2001): Psychotherapie in der Zeit - Zeit in der Psychotherapie. Impulse füü r die Psychotherapie. Band 6. Hannover. Hannoversche rzte-Verlags- Union. S. 49 - 73.

Moreno, J.L. (1939): Psychodramatic Shock Therapy. Sociometric approach to the problem of mental disorders. Sociometry 2

Moreno, J.L. (1945): Psychodramatic Treatment of Psychoses. Beacon, N.Y.

Moreno, J.L. (1959): Gruppenpsychotherapie und Psychodrama. Einleitung in die Theorie und Praxis. Stuttgart

Moreno, J.L. (1970): Das Stegreiftheater (Theatre of Spontaneity) 2nd ed. Beacon, NY: Beacon House

Moreno, J.L. (1975): Psychodrama Vol II. Foundations of Psychotherpy. 2nd Ed. Beacon NY: Beacon House.

Schneider, F., Habel, H., Reske, M., Kellermann, T.., St”cker, T., Shah, N.J., Zilles, K., Braus, D.F., Schmitt, A., Schl”sser, R., Wagner, M., Frommann, I., Kircher, T., Rapp, A., Meisenzahl, E., Ufer, S., Ruhrmann, S., Thienel, R., Sauer, H., Henn, F.A., & Gaebel, W. (2007): Neural correlates of working memory dysfunction in first-episode schizophrenia patients: An fMRi multi-center study. Schizophrenia Research 89, 198-210 .